We take for granted our colourful lives – from the wonders of the natural world, to the myriad objects we use every day – but most people never pause to consider the origins of those colours. But if you’ve been following our recent colour drops, you’ll know that every pigment has a fascinating history.

And perhaps none more so than Prussian Blue which caused a furore at the time of its accidental discovery, and without which, archetypal artworks like Van Gogh’s ‘Starry Night’, or Hokusai’s ‘Great Wave’ would probably not exist.

OUT OF THE BLUE

This resulted in a byproduct called ‘iron ferrocyanide’ – more commonly known today as ‘Prussian Blue’ - the world’s second synthetic blue pigment after ‘Egyptian Blue’.

Until the 1700s, blue was a colossally expensive pigment. Made from crushing semi-precious stones such as lapis lazuli, and costing more than gold, it was sold by the drop. Yes, really.

As with any colour, there were several shades available at the time such as indigo, azurite and the most prized blue of all - ultramarine - which were so expensive and difficult to acquire that they were mostly reserved for portraits of royalty and Jesus. Case in point, the Sistine Chapel, for which Michelangelo had demanded unearthly quantities of ultramarine in 1512.

That all changed somewhere between 1704 and 1706, when, in a messy Berlin workshop, master alchemist and paintmaker Herr Diesbach was busy concocting his signature cochineal red. Alas, halfway-through, he ran out of potash and rushed to buy more from a nearby medic – Johann Jacob Dippel.

But when he added the new batch to his mixture, Diesbach realised that something was amiss. Instead of turning a brilliant red, the substance acquired an unfamiliar pinkish tint. Baffled, he tried to boil it down and watched in consternation as his mixture turned lilac and finally a shade of very deep blue.

Slightly bewildered by this unexpected result, Diesbach went back to Dippel to enquire about the potash. Dippel admitted that he had used it earlier to extract bone oil.

Suddenly, the penny dropped for Diesbach. He realised that the traces of blood had contaminated the potash with calcium ferrocyanide. This resulted in a byproduct called ‘iron ferrocyanide’ – more commonly known today as ‘Prussian Blue’ - the world’s second synthetic blue pigment after ‘Egyptian Blue’.

WHY SO BLUE?

Prussian Blue became synonymous with Picasso and ushered in his famous ‘Blue Period’ – a time that followed the suicide of his close friend.

The recipe was kept secret for the next 20 years, making a handful of people a lot of money in the process, though sadly not Diesbach. In 1724 the British naturalist John Woodward finally got his hands on the recipe and published it in the public domain.

Now the pigment was accessible to anyone, although the exact chemical reaction still wouldn’t be understood for over another century.

By the 1750’s Prussian Blue (also known as Berlin Blue and Iron Blue) was widespread throughout Europe – it was ten times cheaper to produce than ultramarine, and unlike many other pigments at the time, was non-toxic. It also boasted very high pigmentation and could be easily mixed with other pigments to procure new colours.

Many famous artists of the time quickly came to favour Prussian Blue including Turner, Monet and perhaps most famously, Van Gogh. It’s even said the impressionist, Paul Cezanne, loved the colour so much he even used it to dye his moustache.

At the turn of the 20th century, Prussian Blue became synonymous with Picasso and ushered in his famous ‘Blue Period’ – a time that followed the suicide of his close friend. Picasso was in emotional and financial turmoil and the cool blue was the perfect hue for his outpourings of melancholia.

THE NEW WAVE

The colour was new and exotic and added a great amount of depth to the traditional woodblock prints, causing quite a sensation.

By the 1820s, Prussian Blue had reached Japan. The colour was new and exotic and added a great amount of depth to the traditional woodblock prints, causing quite a sensation. Prior to this, the blues used in Japan came from natural plant extracts, which faded fairly quickly and turned a yellowish orange.

The bold use of this colour by the Japanese, coupled with the foreign themes and landscapes, led Europeans to believe this was a new pigment, which they promptly christened ‘Hiroshige Blue’.

It wasn’t until many years later that they discovered that ‘Hiroshige Blue’ was in fact nothing more than good old Prussian Blue, exported to Japan just 40 years prior.

The pigment was also spiking an interest amongst non-artists, including the famous English astronomer Sir John Herschel. He discovered that Prussian Blue has unique qualities of light sensitivity, and that by drawing on tracing paper over another layer with the pigment on it, he was able to make copies after exposing them to light.

These cyanotypes were the original ‘blueprints’ – the predecessor of modern photocopying.

BLUE MURDER

Cyanide is a deadly compound which, if consumed in large enough quantities, can lead to coma and death by asphyxia.

But Prussian Blue has a darker side too.

Swedish chemist Carl Scheele found that by mixing Prussian Blue (iron ferrocyanide) with sulphuric acid, a new acidic, colourless, water-soluble gas is formed which we now know as cyanide, from the Greek word ‘kyanós’ meaning ‘dark blue’.

Cyanide is a deadly compound which, if consumed in large enough quantities, can lead to coma and death by asphyxia. Something the Nazis harnessed to execute over a million victims in their gas chambers before, ironically, using it on themselves after the Nuremberg Trials.

Despite being linked to cyanide, Prussian Blue does have its medical uses including pathology tests for bone marrow and as an antidote to radioactive poisoning.

In fact, it plays such an important part in medicine that it’s listed in the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines. But be warned – it can cause bright blue stools!

DON'T GET THE BLUES

In psychology, blue is associated with reliability, stability and serenity – so much so that it’s even been known to lower pulse rate and body temperature.

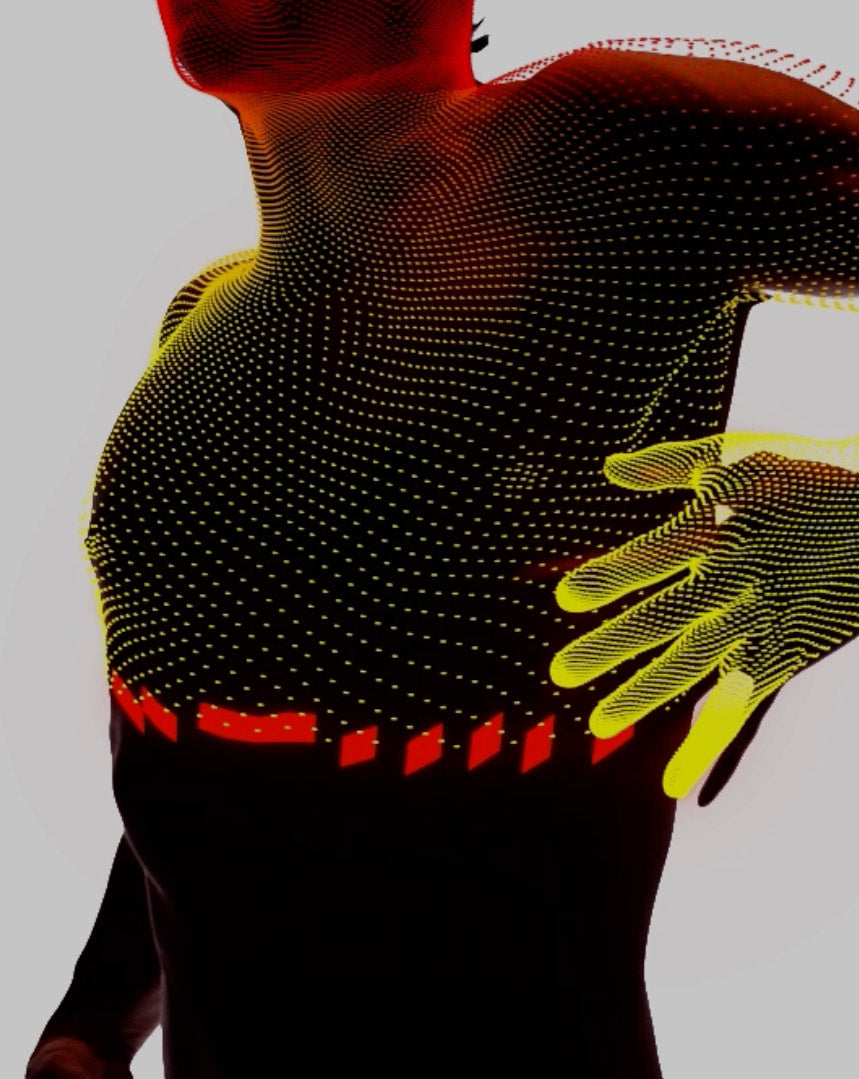

Speaking of pulse rates, yours is about to go through the roof. Why? Because your fave Magic Fit® Tee is now available in limited edition Prussian Blue. But you better hurry, because if you miss out you’ll no doubt get the blues.