You may not know the name, but you definitely know the colour.

Think verdigris, think the Statue of Liberty. Interestingly, the Big Apple’s neoclassical goddess didn’t always wear a blue-green gown. With her proximity to seawater, it took the atmosphere three decades to turn her pure copper to iconic verdigris. Her precious metal skin copped a coating of copper chloride (try saying that fast), and that’s the colour you see today.

In modern French, verdigris translates to 'green of grey,’ and the colour itself is no less complicated. Sometimes called copper green or earth green, verdigris is not a single, defined hue but rather a little bit magic – a meet-cute between copper and oxygen. The O2 strips electrons away to expose copper atoms, so they're free to mix n' mingle with other particles in an endless, ever-evolving dance.

And to this day, little by little, Lady Liberty continues to change.

The colour of chemistry

All the components are in an ever-changing and complex electrochemical reaction equilibrium that’s dependent on the ambient environment.

Verdigris is no new kid on the colour chart. The original ‘turquoise’ has been used since prehistoric times, although it's not a chemical material unto itself; it's a common term for a group of copper acetates. A moveable feast: it's blue, and it's green at the same time.

The same oxidation of copper responsible for the signature colour of Lady Liberty also, fittingly, adorns many Parisian roofs. The romance of the French capital lives in everything from its bridges and streetlamps to its gardens and green skyline. And just as the meaning of words shift across time, verdigris keeps the rooftops of Paris alive. Pretty poetic.

So how's it made?

Historically, people hung copper plates over hot vinegar in sealed pots until a coating of solid green covered the copper. This was then scraped off, dried and ground to form a powder. Later on, people stuck copper strips with acetic acid to a wooden block which was then dug into manure and unearthed weeks later to scour off the verdigris.

You (literally) can’t make this shit up.

Chameleon colour

The fact that verdigris is an exceptionally changeable pigment is its most fascinating aspect. All pigments change somewhat over time, but verdigris can have wide mood swings.

Change is the only constant. You know the saying because it's true, and verdigris embodies the fact that nothing lasts forever.

Is this verdigris’ greatest flaw? Maybe, but also its greatest quality: a colour which never takes a permanent seat at the tone table has a fragile beauty. This fleeting hue holds an inherent fickleness – the chemical reaction which creates it never actually ends. And because it's composed of solid crystals, verdigris isn't one-dimensional – you look into the colour rather than at it.

Just as in an ever-expanding universe, light stretches and colours change – so does verdigris – so much so, you can't assign it a hex code. Instead, it's a shifting spectrum based on where and how it was made. On its surface sits transforming molecules, a coexisting of now and then.

You could say verdigris is the colour that can’t commit.

Portrait of a pigment

Paintings need green – even though it’s not a primary colour, it’s everywhere in nature.

In the Middle Ages, verdigris was one of the only vibrant green pigments an artist could put on their palette. But it wasn’t until the Renaissance that verdigris became the ‘it’ colour for bringing out brilliant greens in a landscape. Unfortunately, verdigris was also toxic, and its growing usage came with an increase in poisoning (nausea, anaemia, or death).

Considered a fine material, it was super-spendy, so people in power appointed revered artists like Botticelli to paint with it. Expensive as it was, verdigris was also known to be unstable and using it knowingly lent any artwork to mortality. Artists knew their painted piece would ultimately perish – as a mirror of nature, the grass pales, and the leaves turn. In the end, everything vanishes; fabric, paint, beauty, life and over time, these paintings transformed, with their radiant greens moving to dull greys and browns.

Despite its flaws, this colour was worth it – from Europe to China – it was in vogue for hundreds of years until it was superseded in the 19th century by more stable bright green pigments like Scheele's Green, Emerald Green and Viridian.

The original colour of feminism?

"The history of women’s work frequently details menial tasks, arduous labour, health risks, inadequate wages, and limited opportunity. But the verdigris industry in 18th-century France is a success story – a financial golden age when many women became entrepreneurs" – Reed Benhamou

During the Middle Ages, European verdigris production was centred in Montpellier, within the Languedoc wine region of France. As luck would have it, wine + copper = verdigris; a reaction reminiscent of wine's oxidation process.

Households here became verdigris hotbeds, with people using the by-products of the wine industry to make the vinegar that created verdigris. During that time you’d be hard pressed to find a cellar in Montpellier that didn’t have copper plates stacked in clay pots filled with distilled wine.

What’s more interesting is that women governed the production of verdigris, very much contrary to the rigid rules prohibiting them from skilled labour at the time. Not only did verdigris creation flourish as a women-run enterprise, but pigment mastery was passed from mother to daughter, creating an industry that women used to gain autonomy.

But is autonomy worth a death sentence?

You may recall that verdigris is a poison. But even more curious than the industry structure was the fact that the women making the verdigris were not sick. Nada, bupkis, diddly-squat. Even though they spent their days covered in verdigris powder, they were in excellent health.

In the 19th century, scientists studied the health of these women and found that exposure to wine fumes every day gave the women immunity to verdigris’ virulence.

Yep, it’s official: wine saves lives.

Clothing with chemistry

Verdigris is versatile, and so is the significance of this colour. Not quite green, not quite blue; it was turquoise before turquoise was a thing.

With its inherent vivacity, this fungible hue is associated with renewal and rebirth. Entirely fitting for a continually changing colour.

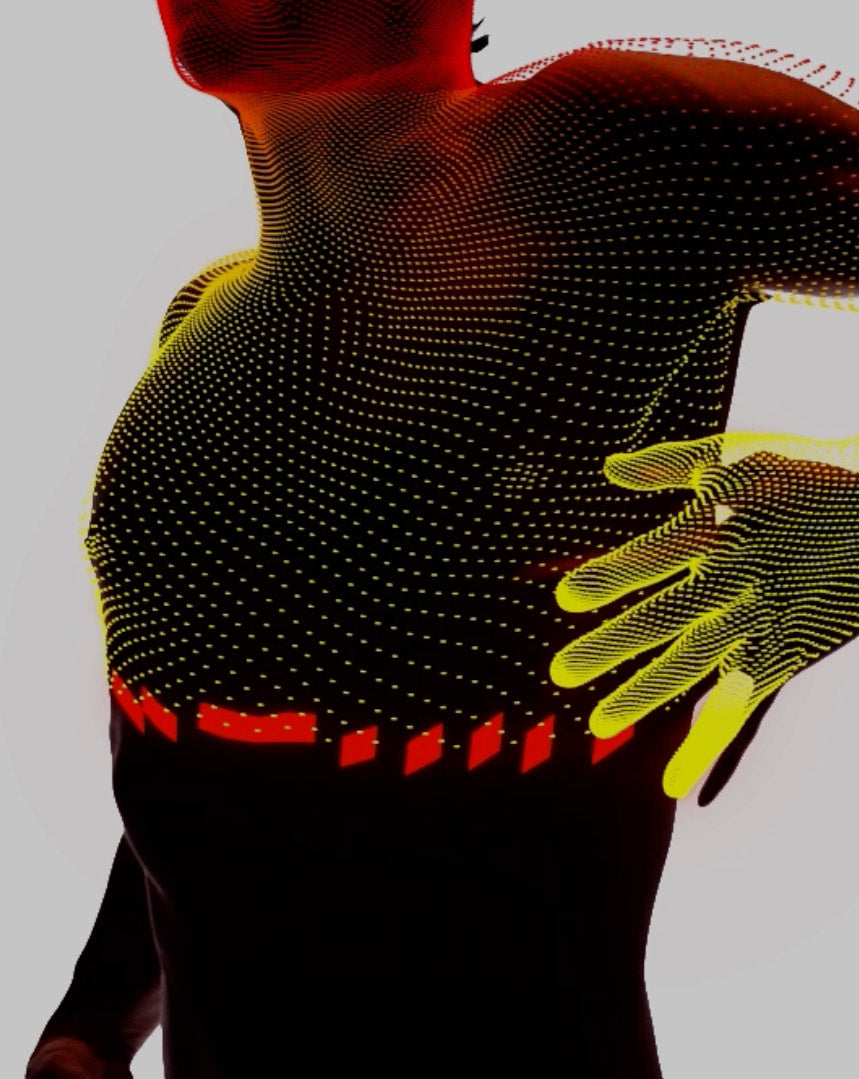

So if you're looking to reinvent yourself, make like Madonna and grab a Magic Fit® Tee in limited edition Verdigris.